Afonso Rocha

Afonso Rocha (b. 1999, Portugal) lives and works in London, UK. He completed his BA (Hons) at the Porto Faculty of Fine Arts, with a semester-long stay at the École des Beaux-Arts de Paris. He is currently enrolled on the MAFA course at City & Guild of London Art School (2023/24) as a grantee of The Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and The Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation.

Recently, he was selected for the 36th Issue of the ArtMaze Magazine and featured in the 4th Issue of the London Paint Club Magazine. In 2023, he was shortlisted for the Jackson´s Painting Prize, exhibiting at the Bankside Gallery, London. In the same year he was awarded an Innovate Artist Grant Honourable Mention (USA) and won the D. Fernando II Painting Award (PT). In 2021, he co-founded O Bueiro, an independent art space and studio in Porto.

His work has been included in multiple group shows in venues such as the Bankside Gallery (2023), Maia Art Biennial (2023), MU.SA – Sintra Museum of Art (2023), D.C. Gallery (2022), Aveiro Art Museum (2022), Universidad Nacional de las Artes, Argentina (2021) and is held in public and private collections in Portugal, UK, Spain, France, Brazil and Luxembourg.

Hi Afonso, tell us about your background. How and when did you first start to paint?

I was born in Porto, Portugal. My parents are both art teachers so drawing and painting was something we used to do quite a lot at home. Even though I always liked drawing, what I truly enjoyed was colouring. When the time came to chose what to study in high school, I decided I wanted to do something art related, and so I enrolled in an art school. Slowly, I started to lean towards painting. I remember going through a book on Lucian Freud and thinking “this is what I want to do”.

Can you explain how your background, including your academic journey at the Porto Faculty of Fine Arts and École des Beaux-Arts de Paris, has influenced your artistic practice?

I studied my BA (hons) at the Porto Faculty of Fine Arts. That was where I really learned to draw and paint. They had quite a traditional approach. In the first year, I remember making hundreds of drawings: outlines, diagrams, quick sketches, long studies… a bit of everything. In the painting studio it was the same, we were trained in doing still lives, portraits, live model, landscapes… all the classics. Looking back, even though it was demanding, it was incredibly important, as it gave me a solid set of technical skills that later allowed me to explore and break the rules I wanted to.

Paris was something else! It was the first time I lived outside of Portugal, and I was just baffled with how much was going on. I used to go to museums and exhibitions almost every day. I got to see all the big names, Picasso, Manet, Cézanne, Gauguin, among so many others. Furthermore, the school was great.

How do you begin to work? What is your process like?

I tend to work with bodies of work and so, when I have finished one, I already have an idea in which direction I want to move next. So, the first thing I do is to collect visual and conceptual elements that interest me. Old photographs, recent photographs, paintings I’m interested in, drawings, images from the internet, TV, or Instagram. It doesn’t really matter where they come from. What I try to do is to get access to as many images as I can, so that I have the tools to build what I have already pictured in abstract.

However, this process does not stop once I have finished the first draft of the compositions I’m going to work on, it is something I do daily. I’m always on the lookout for images and ideas and I build an archive around them.

The layered approach in your art practice, akin to a collage, is interesting. Can you delve into the process of how you select and incorporate different layers of information, references, and ideas in creating your compositions?

I think the word “collage” is really embodied in my practice. It relates to the way I think and create. I use already existing imagery to give life to ideas, but this imagery also informs the ideas themselves. Instead of starting with a blank page I start with a set of constraints I have to work with. That can be quite stimulating.

After that, is just a process of composing with what you have. I try to find tensions I like, possible narratives or simply compositional shapes. It’s a game between form and subject matter. There is, of course, a big amount of chance into the mix, as everything would go differently if I had slightly different references from the beginning, but apart from that I’m quite lucid in the way I compose. The process usually takes a couple of months, because I can’t stop changing them, and even then, after deciding they are ready to go, I tend to keep going back and forth, altering small things.

You mentioned that your work questions painting as a dialogue and legacy. Could you discuss specific instances or works where this dialogue is particularly pronounced?

I think as painters we are always dialoguing with the past, either we want it or not. There are thousands of years of history of art, of history of people creating images… how can we ignore that? What I try to do is to use all those images, all that history, as material to be shaped and rethought. When you decide to quote or evoke things from the past, or from other people’s work in the present, you have no option but to do it in a critical way. Its all about using what’s already there to say new things. It is, once again, a process of collage.

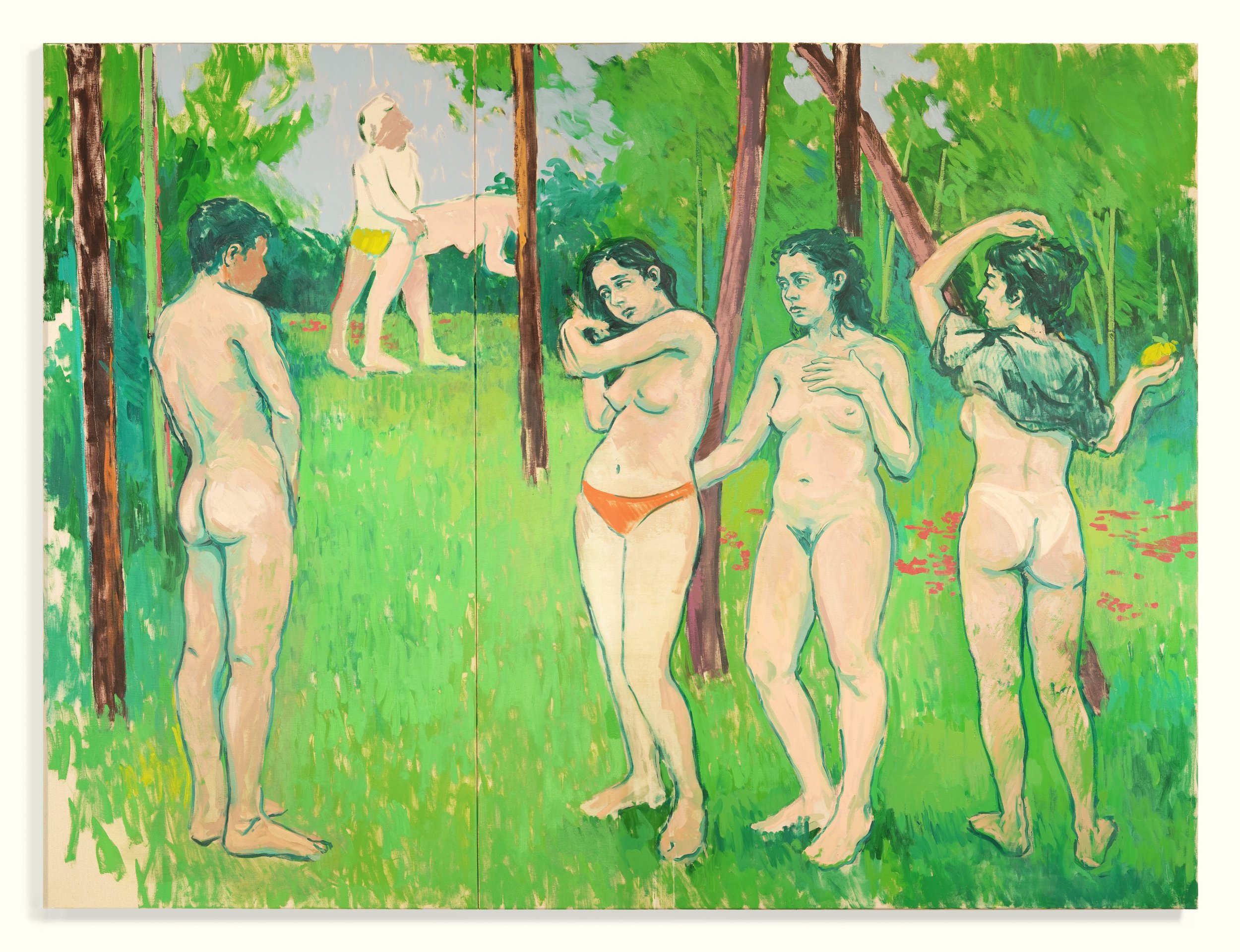

If you look at “The Toilette” for example, a large painting I did between 2022 and 2023, the three figures in the foreground are an obvious echo from the history of art, from all those scenes where Venus is being groomed and dressed by other nymphs, ready to be showed to the other gods (or men). It’s a quite common mythological theme and dozens, if not hundreds, of its representations can be found. But what happens when you make it into an everyday scene? When instead of gods and nymphs there are simply people, naked, awkwardly standing in a garden? It becomes something else. It’s not just a parody, which usually turns to be quite uninteresting, but a whole new conversation, a new image.

The influences you mention, from literature to social media, play a role in your visual concepts. Can you share specific examples of how these diverse sources manifest in your artworks?

I think it is just a question of “permission”. A question of what you allow yourself to use as sources for references and subject matter. Of course, each of us has its own research, but that doesn't mean you need to limit the places you take from. So, if I feel that it makes sense to, in the same painting, mix a flamingo inflatable that I saw on amazon and a reference to a Goya early painting, as it happens in one of the paintings I’m currently working on, I will do so.

The references to classical and baroque genres in your paintings, like the Fête Galante or the Bacchanalia, suggest a connection to art history. How do you navigate the balance between tradition and contemporaneity in your practice?

It is a difficult balance. I recon that when I started, I tended to lean a bit too much towards the history side. With time, I got further away from it, now using tradition as a tool to think contemporaneity. History functions as a cultural background without which it is quite difficult to understand and contextualize the present. It’s like a chain…to insert a new link you need to connect it to the previous one. The idea of creating in a void, often associated with the word “originality”, has always struck me as a somewhat naïve concept.

The juxtaposition of intimate matters, recollections, and contemporary imagery in your work is fascinating. Could you discuss a specific artwork where this combination is particularly prominent and its significance?

I believe all my works draw from personal experience. They always delve into subjects that, at the time I make them, I find myself thinking about. However, I believe its important to let the paintings follow their own path, to let them have their own existence away from us. Because otherwise, the work might become only about you, about your personal experience, or even just therapeutical, which I think it never should be. Knowing this, what I always try to do is to allow for my personal experiences (my thoughts, concerns, and recollections) to turn into something else. I want the paintings to feel very personal and yet like they’ re not mine, like they don’t belong to me.

There’s a painting I did in 2021 called “Delilah” that is still, to this day, one of the paintings I did that I feel closer to. I have sold it along the way, but sometimes I wish I could have it back so that I could be with it just one more time. I believe that’s because it was the first time I truly allowed my work into my life, or maybe the other way around. Anyways, I think it is a good example of trying to combine intimate matters with both historical imagery and contemporary concerns.

The use of large canvases in your paintings is highlighted in your works. How does the scale contribute to the narrative and impact of your artworks, especially in relation to the intimate or trivial subjects you portray?

Not only I enjoy painting big, which is definitely a different feeling and exercise, as it is also often crucial in my practice. I try to make the figures close to real life size (usually slightly smaller) because that way I can force the viewer to be part of the painting. Its my way of telling them that I’m painting about the world around them, I guess. The paintings then become something more involving, something you cannot escape, even aggressive maybe. If they were small the viewer would feel like passively looking through a window, as one does when confronted with a Bruegel or a Bosh for example. Instead, I want them to feel like they are part of it. I want them to feel the tenderness, the aggression. To feel awkward or discomforted, or confused. Ultimately, I want people to feel the paintings and think about the paintings, instead of looking at them. Its like watching the same film at home or in the cinema.

The mention of the grotesque of the male gaze and questioning stereotypical roles in your paintings suggests a thematic exploration. Can you elaborate on how you approach these themes in your works and their significance to you?

Questions of intimacy, gaze, sexuality, sexual politics, amongst others, are often present in my practice. I find these topics extremely interesting sources of social and emotional complexity. We tend to make things into black and white only, even if they are anything but that. Love, intimacy, tenderness, aggression…we try to make it simple, to separate the good from the bad, the healthy from the unhealthy. We know what to approve, what to frown upon, but in life things tend to find a way of being everything but what they should.

Simultaneously, by dialoguing with the heritage of western art, I try to critically present and recontextualize the things we see in past imagery and confront it with today’s readings and understandings of the world. What happens when a faun chasing a young nymph becomes just a regular man chasing a young woman? Or when poor Susanna, from the well-known Susanna and the Elders episode, becomes a man? Small visual changes can provoke abrupt shifts from heroic/historical to awkward or discomforting. Through these dialogues in time, I try to explore contemporary conversations around intimacy in this broader and contradictory context.

How has the city you live and work in influenced you and the art you create?

Coming to London had a huge impact on my life and my practice. I’m originally from Porto, a not so big city in the north of Portugal. There, the museums are almost nonexistent, there are only a handful of good galleries, and painting is, to say the least, out of fashion. When I first moved here it was like living in a dream. It still is most of the time. It is the most exciting thing to be part of a non-stopping conversation, a dialogue between so many people, from all places, that are thinking and rethinking painting, creating new approaches and presenting new perspectives on what painting can be.

I quite identify myself with the British art context, which is, no doubt, so diverse and multicultural. Not only painters like Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, or David Hockney, were fundamental references during my education, as I have also found in contemporaneity a big net of artists I admire and follow. Above everything else, I believe moving to London has allowed me to become part of a larger dialogue, a contemporary conversation that I wasn’t so aware of before.

Describe a real-life situation that inspired you.

Some years ago, when I started to paint more seriously, my father told me something I later read in Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet. He said “Only do something if you need it. Only paint if you feel that’s important to you, if you can’t go without it.” Because if it doesn’t move you, if its just “work” … well, there are better things to do, really.