Matthew Hansel

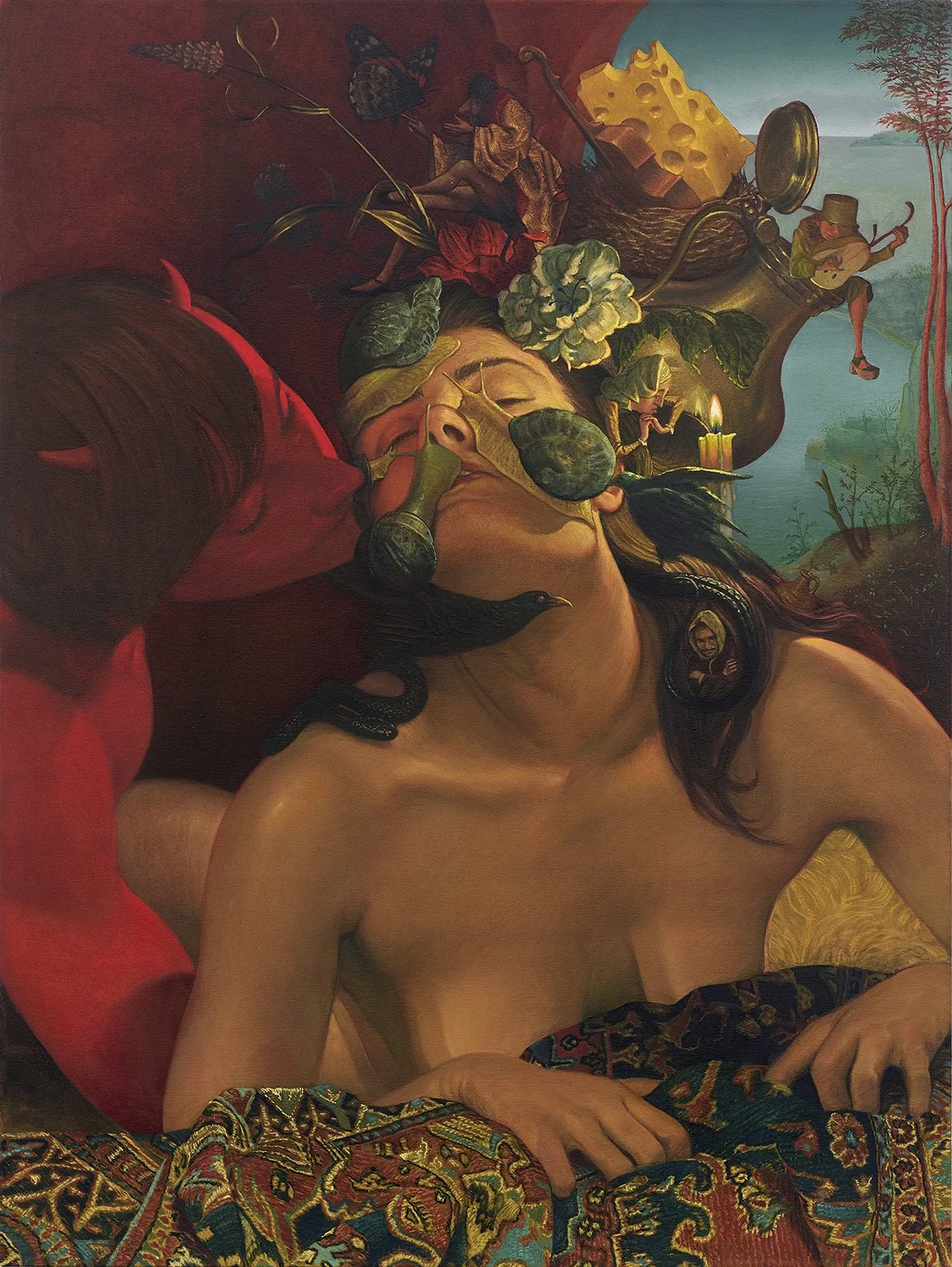

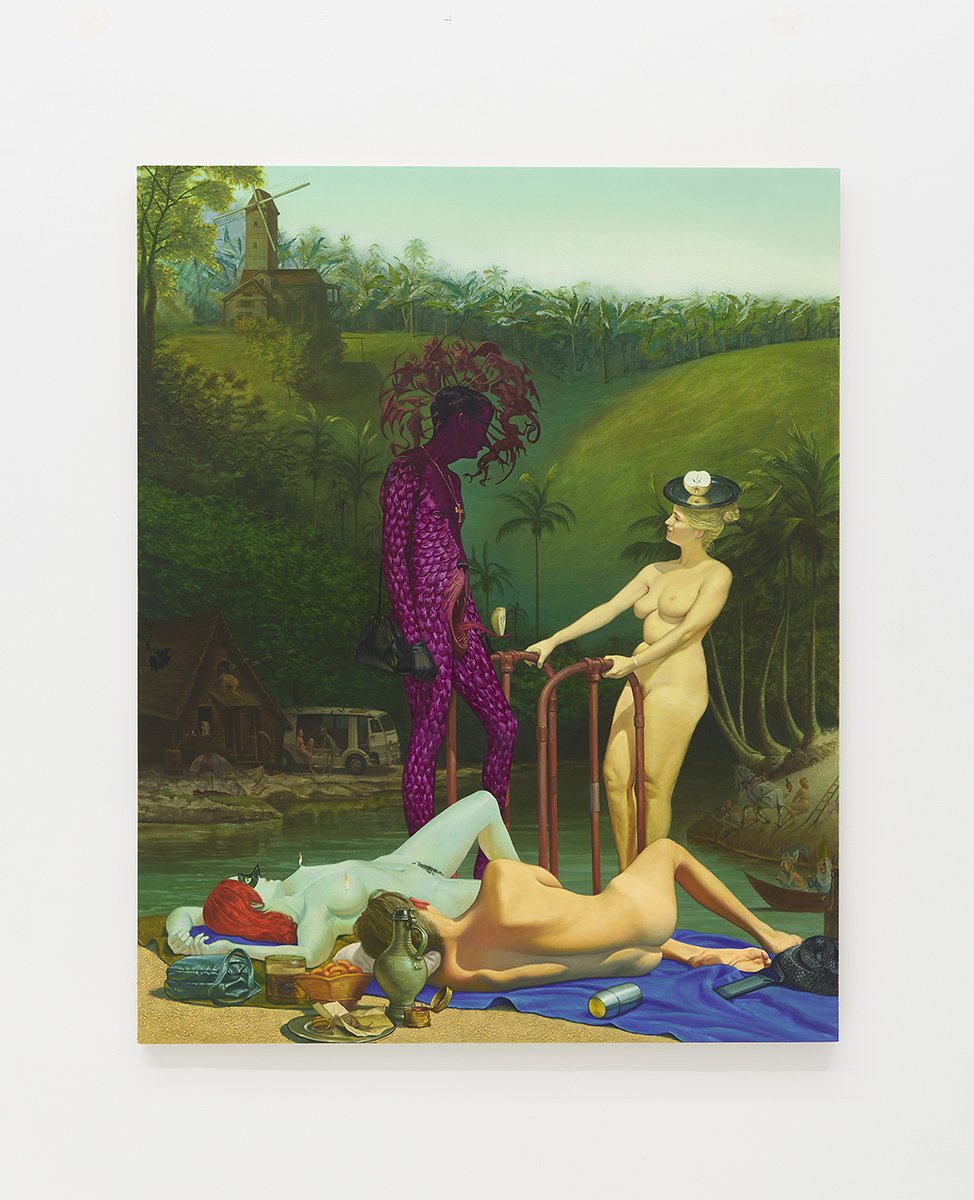

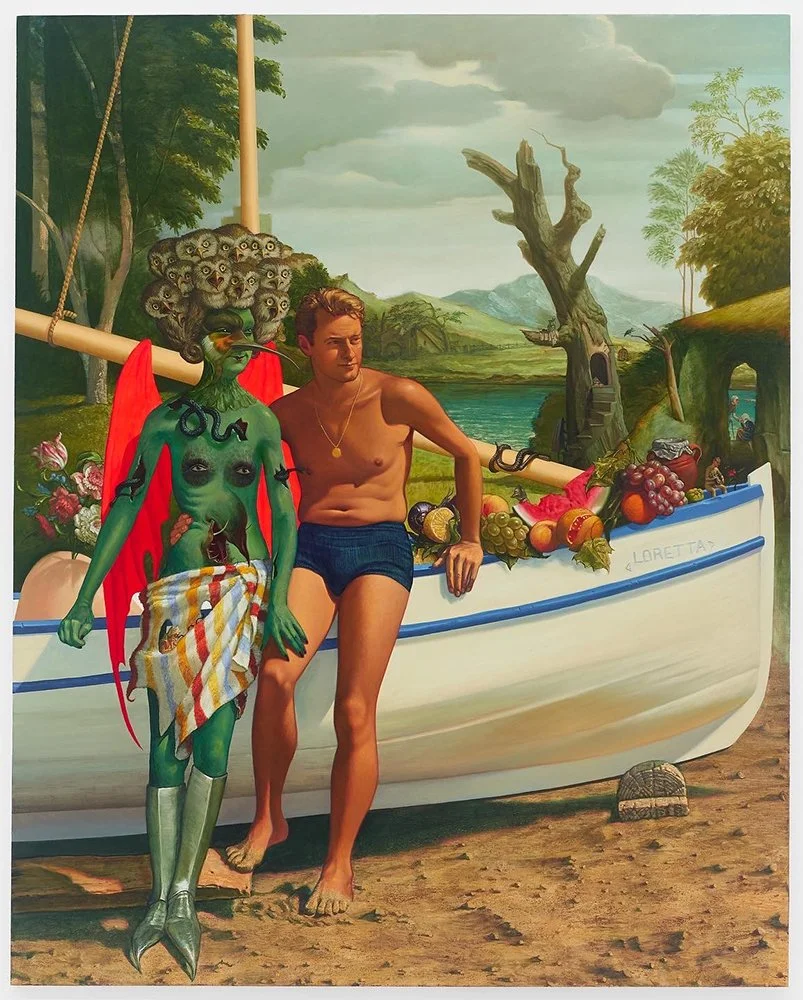

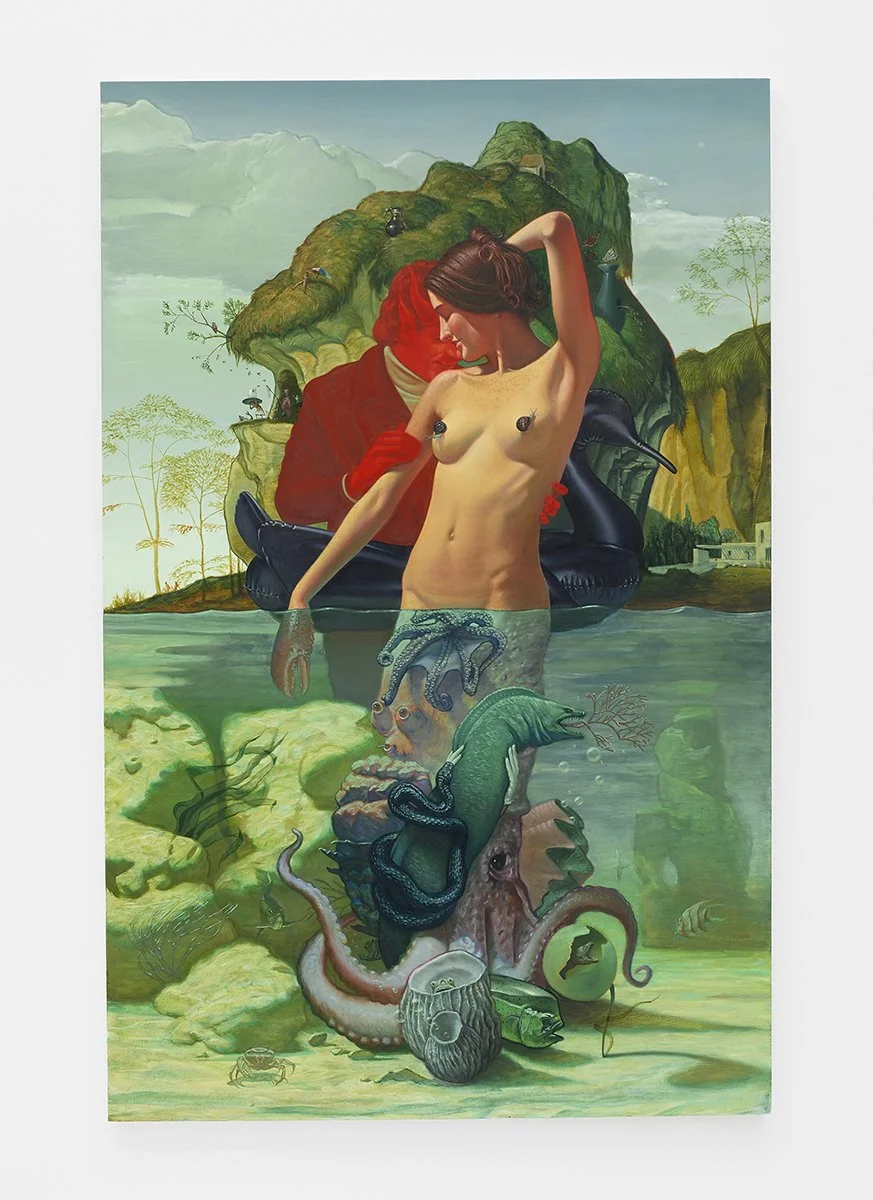

Matthew Hansel (b. 1977, Virginia) is a painter and visual artist whose work focuses on the paradoxical relationship the human condition has toward the grotesque — both repulsion and attraction. This tension is embodied through his vivid portrayals of inner demons. He earned an MFA from Yale University School of Art and a BFA from The Cooper Union School of Art. Hansel has exhibited nationally and internationally, with solo shows at Rodolphe Jannsen (2024), The Hole, Los Angeles (2023), The Hole, New York (2021), Brand New Gallery, Milan (2018), PM/AM Gallery, London (2017), Wasserman Projects, Detroit (2015), and Yuka Contemporary, Tokyo (2010). He received a grant from the New York Foundation for the Arts in 2011 and has been part of the White Columns Artist Registry since 2017. His work has been featured in publications such as The New York Times, Artforum, Blouin Artinfo, Vice, Time Out New York, The Brooklyn Rail, Art Now LA, Purple Magazine, and Brooklyn Magazine. The first monograph of his work was published in 2023 by Anteism Books. Hansel lives and works in Brooklyn.

Matthew Hansel's works is featured on the cover of Issue 8 of Artsin Square magazine, and his interview is also included in this issue. Learn more

Hi Matthew, tell us about your background. How and when did you first start to paint?

I first started oil painting around the age of six or seven. My mom found a local artist who was willing to teach me on the weekends. My mom would drive me over to her studio on Saturday mornings and I would walk into the sliding glass door around the back of her house. It was out in the woods and she used her basement as a studio. It was cramped with stacks of paintings and smelled of stale cigarette smoke. Eventually, she would come walking down the stairs holding a cup of coffee and wearing her bathrobe. I learned how to mix oil paint, blend colors and spent weeks copying a Norman Rockwell painting. It was great. She was a bit unhinged but I readily overlooked her manic energy because I thought she was a magician. To a young kid, the things she did with paint were unimaginable and her lifestyle completely foreign. It felt a little dangerous and thrilling when I entered her basement studio in the woods – which is the way painting should feel. Thinking back, that sliding glass door was a metaphor really. It was a portal into an unfamiliar world and I think artists are constantly looking for them. The process of finding them is always opaque until it’s painfully obvious. It’s like trying to find a station on an old radio. It’s mostly noise and static with glimpses and snippets of voices and melodies which come into focus for a moment or two and then recede. It is the struggle and joy of the artist to suddenly hit a frequency that penetrates the uncertainty; rising up through the noise, emitting a sound so clear and true that the soul need but follow it.

How do you begin to work? What is your process like?

Every painting is a dance with the past and try as they might no painters ever dance alone. I’ve always embraced this intractable dynamic in my work. I think it’s one of the things that makes painting so special and dare I say romantic – knowing there is always a partner stalking the edges of the dance floor, waiting for you to make a move. When you boil it down, painting is a wonderfully archaic process. You mix colored powders with oil then attach animal hair to the end of a stick. Finally, you find a piece of fabric and you’re off. I doubt there is another method of art making which is so simple yet able to elicit such emotion. Having said that, I don’t ignore the advantages afforded to me in the present day. I use Photoshop to make digital collages where I can easily build my compositions and quickly make small changes until I’m satisfied. I keep many folders of images that I pull from all sorts of sources; photos, scanned book and magazine pages, drawings, etc. I usually start with a quick sketch or by simply jotting down an idea. It can be something as innocuous as “Playing beach volleyball with your demons in a snowy landscape.” It’s then a matter of assembling images. The process of collaging them in Photoshop is very playful and allows me to accomplish a completed composition and make most of the adjustments before I start the painting. I use this process for the main composition. Once the painting starts, I begin adding the smaller figures and tiny worlds. I think of this as creating microcosms within the macrocosm. It’s a way of rewarding the viewer who sees the painting in person as many of these details can’t be seen via JPEG or on a phone screen.

Your work explores the tension between attraction and repulsion in the grotesque. How do you navigate this paradox in your painting process, emotionally and visually?

The human condition allows for a paradoxical reaction to the grotesque: the dual emotions of repulsion and attraction. Art as a medium is uniquely adept at allowing us to engage in this contradictory response because it acts as a scrim through which we can observe ourselves. The act of seduction is often decoupled from rationality and through art we can be attracted to that which if seen in the flesh would repulse us. It’s a special power – one of many art possesses. I approach painting as a seducer; someone looking to engage the viewer on a psychological level, luring them to revel in the aberrant. My paintings start with the assumption that we’re doing it wrong. They depict an alternative way to deal with our demons, a world in which instead of hiding from or repressing them, we embrace and learn to live with them – not just coexist, but take them out on the town and show them off.

You write about being “seduced by demons” and embracing the abject. How do you determine the boundary between seduction and revulsion in your compositions?

I don’t think of it as a boundary. It’s not like images sit on one side or the other. The truth is, I’m seduced by painting – the demons are just along for the ride. What I mean is, there isn’t anything that can’t be seductive if presented in the right way. It’s the method of delivery. A spoon full of sugar makes the medicine go down. The way a thing is made can be felt by the viewer and changes the way they see and feel about the thing. If an object is imbued with care and effort and humor – it’s very hard not to be attracted to it. I just do my best to make my paintings want to be looked at.

Bosch’s work re-emerged as meaningful to you during the pandemic. What specifically about that time shifted your perception, and how did it influence your recent series?

It was during the lockdown in 2020 when I first started making my current body of work. We were all at home stuck on our couches and stressed about what was going on in the world outside. It seemed to me that we were all trapped inside with our inner demons. I remember having a vision of a demon sitting next to me on the couch, doom scrolling. I thought that if we could just take our demons out for a stroll or on a trip to the beach, we would all be better off. So, in an act of catharsis, I made a painting of a young couple splashing in the waves with a demon. It was an odd painting for me and led me to think about the power art has to seduce us, especially when this power is used to present the grotesque in a way that is seductive. Bosch is a master of this – he allows us to revel in the most sadistic and twisted acts. Take another look at his triptych, The Garden of Earthly Delights. Notice how much time your eye spends searching the crowded right panel. It’s an underworld filled with torture, fire, death and excrement. He makes you want to put your nose against the painting to see every detail. Then notice how little time you spend on the left panel – his tranquil version of Heaven on Earth – it’s a real snooze fest. His miniature worlds of cheeky depravity convey a morbid splendor and frankly, the demons seem to be having a lot more fun.

You reference Dawkins' concept of the meme as an infectious idea. Do you see your paintings functioning similarly—as visual “memes” that carry affective or psychological contagion?

Paintings are the antithesis of memes. They are almost singular in their refusal to spread virally – that’s what makes them romantic and insane. They’re personal, self-contained and archaic; hard to move; non-transferable. They can’t be reproduced and are usually attached to walls. You have to go somewhere to see them. If you want your idea to spread, making a painting is possibly the worst way to do it. Painters are still carving their ideas on stone tablets and hoping to get viewers to climb the mountain to see them. This act takes an immense faith in humanity and a belief that fellow travelers will find their way to stand in front of a thing you made. However, in an odd turn of events (caused by today’s social media driven art world) images of paintings do spread in a way they never have before. This makes them much more meme-adjacent. But, these images are just tiny pixels on a screen and are pale illustrations of the paintings they are depicting… or so every artist hopes.

Related Pages

Meet the Artist

Joe Hedges