Rei Xiao’s work inhabits autobiographical imagery interwoven with dreamscapes and chimeric figures, layering meaning and narrative both within and beyond the frame. Drawing from her Chinese-Turkish heritage, she explores hybridity and in-betweenness, projecting her inner world onto objects and animals. Through painting, she delves into realms beyond trauma, perceiving darkness as a zero point in a vast coordinate system. Rei navigates the tension between being immersed in and setting out from that darkness, seeking the lexicon of her consciousness. Using whimsical and morbid narratives, she creates stories grounded in reality that transform into various planes of existence.

Rei Xiao

Artist Statement

I make autobiographical works that merge dreamscapes with chimeric figures, layering narratives within and beyond the frame. Drawing from my Chinese-Turkish heritage, I explore hybridity and in-betweenness, projecting my inner world onto objects and animals. Through painting, I navigate realms beyond trauma, using whimsical and morbid imagery to depict stories grounded in reality that evolve into other planes of existence.

Instagram: reixiao

Website: reixiao.com

The good boob and the bad boob, Oil on canvas, 60x68", 2023

Hi Rei, tell us about your background. How and when did you first start to paint?

Hi! I’m a Chinese Turkish artist born and raised in Istanbul, Turkey. I came to the US to study fine arts at Tufts University in Boston and moved to Brooklyn upon graduation. I’m a painter and a tattoo artist. I started to paint in high school, although I have been drawing for as long as I can remember. I began exploring many artists on Pinterest, Tumblr, and Instagram who were painting in watercolor. Back then, watercolor was the most accessible material for me, so I became obsessed with experimenting with it and learning how to master it to render what I wanted to express. After years of longing, I finally learned oil painting in college and experiencing the infinite possibilities it offers connected me even more to it.

How do you begin to work? What is your process like?

My work begins with ideas accumulating and subconsciously morphing into compositions and figures. I like to collect or digitally archive images of art and other objects and let them simmer in my head. I usually sketch a lot of things into journals and start with a pencil drawing of what I want to paint. If my goal is to stay true to the idea and the image I envisioned, I make several preparations and decisions beforehand. I make a thumbnail painting of the composition, transfer it to canvas, and draw the outline with some values, then I start painting. After that, there is a lot of staring at my painting involved as I progress.

You mentioned questioning the validity of reality and exploring layers within consciousness. How does this philosophical inquiry inform your artistic process?

I’ve been reading about biocentrism, a series of books by Robert Lanza, which explains his theories on the nature of consciousness through quantum mechanics. He talks about how time and space are human constructs that don’t exist independently of us, and that reality is a product of our consciousness. Reality doesn’t exist separately outside of our consciousness; we are all a part of it. The books expand on quantum mechanics by explaining terms like entanglement and superposition — it’s a field that tackles the probabilities of how waves and

electrons behave. The idea of reality existing in probabilities and collective consciousness intrigued me the most. My work heavily draws from personal experiences and a need to externalize inner turmoils. Developing a visual language based on lived experiences is how I feel connected with the imagery. I seek solace in exploring and understanding darkness and trauma, focusing more so on their impact than their causes. This often involves placing anthropomorphic figures or self-portraits in unsettling but familiar places that seem to exist outside our material reality. I like to think that this imagery exists in multiple states within realms constructed by a collective consciousness. For some reason, this feels validating—as if I am not alone in my trauma.

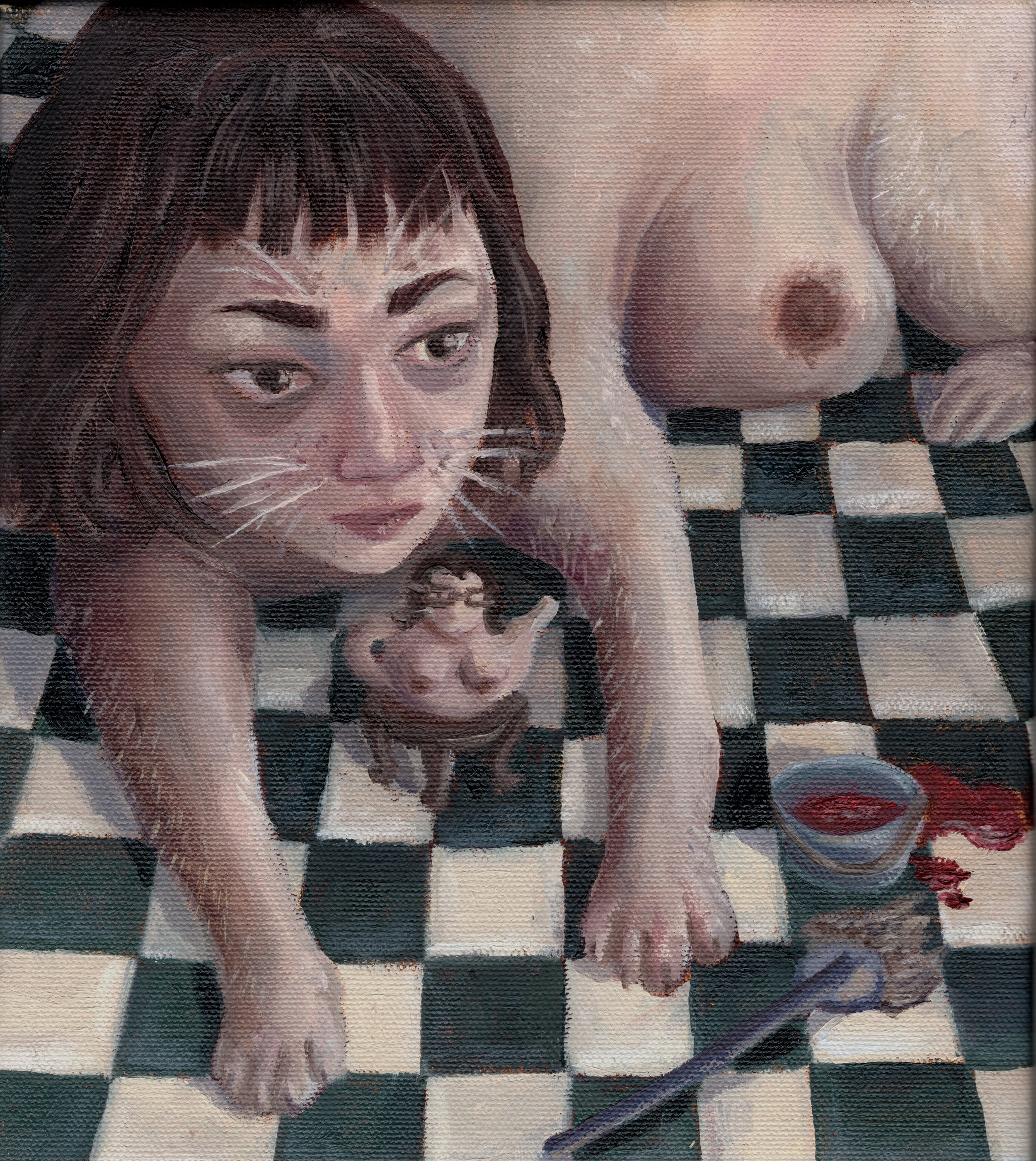

The boob cat, Oil on canvas, 8x9",2023

You mentioned that your process is an exploration of realms outside of trauma and darkness. Could you discuss how you approach incorporating elements of whimsy and morbidity into your compositions?

I think whimsy and morbidity come naturally to me because I am fascinated with dark humor. Merging the playful and almost childlike with the eerie and sinister creates a hybrid imagery that bridges childhood and adulthood. It sometimes feels like these elements aren’t meant to be in the same context, but they are. Most of the autobiographical imagery I use draws from the turbulence of the child within me, who is still stuck in the same memories, and the adult that I am, who can’t nurture this inner child because I’m still figuring out adulthood. This conflict is at the center of my predisposition for incorporating such contrasting elements.

Bosphorus Kittens, Oil on panel, 4x5", 2024

How does your cultural heritage influence your artistic practice, particularly in terms ofdepicting hybridity and in-betweenness?

My mom is Turkish, and my dad was Chinese. I grew up in Istanbul, Turkey, with adistinguishable Asian outlook that separated me from most people. My dad wasn’t aroundmuch throughout my childhood, so I was barely exposed to my Chinese heritage. It wasisolating and overwhelming to look so different from everyone yet be immersed in a culture Ifelt disconnected from. This disconnection fueled my interest in hybridity and in-betweenness. Iam subconsciously drawn to juxtaposition and contrast, much like how some people seekfamiliar environments that parallel their traumatic past.Firstly, Istanbul is filled with immigrants and has a rich history of multi-ethnicities. Despite this,my upbringing always made me feel like I was the only person who looked like they came fromanother planet. The Byzantine and Ottoman empires both conquered and fell apart in this land,leaving behind a legacy that makes Istanbul a literal meeting point of the West and East. It istouching to think that the soil I come from is imbued with hybridity itself.Until I came to the US for college, I grew up with my mom and her 15 cats in high school inIstanbul. Street cats are a big part of Istanbul’s culture, and living with 15 of them in ourapartment was both traumatizing and transformative. I hated it and worked hard to escape thatlife, but I was also living with 15 creatures with distinct personalities. It was like a mixture ofdocumentary, sitcom, and thriller. I saw something very familiar in them that I identified with, and I liked that it was almost humanlike but not quite. Anthropomorphizing them, whether emotionally or in my paintings, somehow helped me come to terms with hybridity.

Could you delve deeper into the symbolism of objects and animals in your work? How do they serve as vessels for projecting your inner world?

I feel drawn to animals because they all have distinct characters, yet we can only make sense of their characteristics through their actions and nonverbal communication. However, there isalso so much we project onto them, often anthropomorphizing them. This creates a fine linebetween what we observe in them and what we attribute to them from our perceptions.The symbolism in my work lies in the subconscious meanings I attach to animals. Rats,spiders, cats, fleas, and birds are all creatures I’ve encountered, and the context of ourinteractions was intriguing enough to explore, distort, and materialize through painting. I livedwith cats and fleas for years, so we have some rapport. I associate the small and, for somepeople, unappealing nature of rats with how I once perceived myself in the world, especiallywhen I was living in Turkey. Spiders show up in my dreams a few times a year and they areomnipresent in the world—factually, we are always within 3 feet of a spider. They are aloof andindividual creatures, similar to cats, and I find them mystical.With objects, it’s almost entirely a projection of memories and associations. Chairs, teapots,sofas, train rails, and so on. They have an enigmatic charm because they embody meanings.Their material forms may not have anything to do with the memories linked to them, butsometimes the form engages in a dialogue with the memories. Teapots, for instance, remindme of my mom due to their shape and my mom’s figure. They hold and serve tea, which Iassociate with my mom’s love language: acts of service.The silhouette of the chairs feels like an animal on four legs. I spent a good chunk of mychildhood in my grandparents’ house where nothing seemed suitable for a child or slightlyentertaining. Staring at armchairs, sofas, or chairs with cabriole or some other wooden textureor fabric pattern was all I had as a form of entertainment. There was nothing to play with, so Iwould stare at things and observe their shapes, forms, and colors. After a while, things start tolook like humans. Chair legs look like real legs, animal or human, and the armchair’s silhouette starts to resemble a curvy female body. In summary, I’d say I project my inner world onto symbols because I feel the need to share my loneliness and bond with forms and shapes that appeal to me.

You described darkness as your zero point in a vast coordinate system. How does thisconcept of darkness serve as both a starting point and a backdrop for your creativeexploration?

The idea of this coordinate system comes from a book by John Lilly, who developed sensory deprivation tanks for his experiments with LSD in the 60s. It was an incredible book, and it taught me that, in times of uncertainty about my life and future, books about exploring the universe and consciousness give me comfort that my soul or consciousness, or whatever you call it, is not trapped on this capitalist planet. In the book, Lilly describes his explorations in the tank on LSD, involving various encounters with unknown entities and a distortion of his spatiotemporal perception—he didn’t have a sense of location, and everything felt much vaster than his human brain could conceive. He mentions that after several experiments, he started to gain more control over these encounters, where he didn’t feel overwhelmed by their presence and could return to his “zero point” to winddown. He describes this zero point as “blackness stretched out to infinity” where he finds calm and peace. While the meaning of this blackness is completely the opposite for me, this is the exact "physical" description I had in mind for whenever I felt overwhelmed by dark thoughts. This is where my consciousness recedes in times of loneliness. I feel like I’m facing this vast blackness and I’m consumed by it. Lilly’s version brought so much more nuance to how I perceive darkness. It made me realize that it is a starting point for many ideas, compositions, and feelings that materialize into paintings. I don’t have to be afraid of it but rather let it guide me into creating new things out of it. Darkness, for me, is both a foundation and a surface to create on. It’s the place where my creativity springs from, allowing me to explore and transform my inner turmoil into visual language.

Baking mommy, Oil on canvas, 61x64", 2022

In what ways do you feel your artwork reflects the tension between being submerged indarkness and striving to find the lexicon of your consciousness? How does this tensionmanifest visually in your work? /How do you balance the immersive nature of trauma with the desire to move beyond it inyour artistic practice? What role does catharsis play in your creative process?

For me, depicting trauma is a means of externalizing it, and once I materialize it through acreative vision, I have more control over my inner turmoil. Creativity and art can be healing, butthey also require confrontation. It’s not just a serendipitous process where you feel much betterafter creating something about your pain; it’s more complicated, and the struggle that comesout of it makes it more empowering.I feel connected with certain imagery or symbolism when I draw from personal narratives. It’salmost like there is an innate intuition that pushes me to tap into trauma. The desire to movebeyond trauma is linked to the desire to leave a mark.

So, the urge to create overpowers therisk of triggering my traumas.I particularly like leaving a mark when it represents me. There is something very powerful abouthaving individuality when you feel powerless against something dark and daunting. Yourindividuality inhabits your memories, your story, your body. “The lexicon of my consciousness”refers to that individuality. The more I can expand on this language, the less I feel trapped in trauma and darkness.

Can you elaborate on how you merge dreamscapes with lived experiences in your artwork? How do you navigate between the surreal and the real? /Can you walk us through how you create compositions that evolve from grounded reality into other realms? What techniques or tools do you employ to achieve this transformation? /Could you discuss a specific piece where you feel you successfully distorted reality or explored something beyond reality? What was the inspiration behind this piece and how did you execute it?

Exploring something beyond reality” addresses our perceptions of material reality, where we have a physical form, a location in the universe, a present, past, and future. I enjoy thinking about and believing in the realm beyond our material reality that we only have access to through our consciousness instead of our body. I’m never fully sure of its existence, but I do feel it.

“Distorting reality” is about recreating elements from our material reality, whether they are memories, places, people, animals, or objects of emotional significance. I find it playful and alleviating to reinterpret these elements on a new surface, have autonomy in how they are represented, and explore their interconnectedness within my consciousness in a brand-new composition. It is very difficult to judge a piece’s success in achieving this distortion or exploration because I do it intuitively, not purposefully. So, it feels strange to quantify it. One piece I can think of is a small oil painting on a panel titled “Bosporus Kittens,” featuring two sphinxes sitting on each continent of Istanbul with the Bosporus Bridge between them. I have been thinking a lot more about hybridity and multi-ethnicity ever since I moved to NYC. There is so much diversity here, and in Turkey, diversity is not acknowledged in the same way. People tend to be micro-aggressive towards anyone who doesn’t fit their definition of a Turk.

I’m Chinese-Turkish, so my Asian outlook always made me stand out throughout my childhood. I was isolated or fetishized in various ways and didn’t realize that it was a traumatic experience until I came to the US. New York City’s diversity somehow reminded me that Istanbul is a city of diverse people with adiverse history. Just like in NYC, people from all sorts of religions and backgrounds live or have lived in this city. The cultural artifacts of Istanbul include a hybrid mixture of the Ottoman and Byzantine empires’ remnants. However, I never felt like I was exposed to this hybrid nature of Istanbul or had a chance to embrace my multi-ethnicity there. Many factors played a role in that, including the political crisis the government brought, especially after religion became a tool of oppression. There was also no such thing as a Chinese or at least East Asian community in Istanbul that I could be a part of.

In fact, I only know 2 other Chinese-Turkish people; one lives in Hong Kong, and one lives in Massachusetts whom I met online because my bio on Instagram said “Chinese-Turkish artist” I could only contemplate all this after I was far away from Istanbul and could observe things from a safer distance. As for the painting, it feels affirming to place myself on both continents of Istanbul as these gigantic sphinx figures. It distorts the reality of the traumas I endured as a Chinese-Turkish woman in Istanbul. In the painting, I’m carrying the vessel of a ubiquitous animal seen in Istanbul, the brown tabby stray cat, but I’m not small; I take up a vast space, even stopping the traffic on the Bosphorus Bridge. There is also a spider hanging from its web in the upper right corner, like an omnipresent being that follows us everywhere, but I can’t tell you how that’s connected to this whole narrative. In short, the painting inhabits the fragments of connections I draw about my past and birthplace, emerging on a new surface where I have the power to dictate the story.

Describe a real-life situation that inspired you.

The most recent real-life situation I was inspired by was when I saw this big wolf spider in Upstate New York at an artist residency. It was Mother’s Day, and I was reading about Louise Bourgeois’ works. I realized I didn’t notice the eggs most of her spider sculptures carry under their abdomens. I decided to look up spider egg sacs and found some images that look simultaneously disturbing and appealing. Minutes after seeing that image, I got out of my seat to use the bathroom, and in the hallway, I saw this huge wolf spider carrying an egg sac. Isn’t that so strange? I keep thinking about it.

Everything is a joke to fleas, Oil on Canvas, 37x41", 2022

Flea parade, Oil on canvas, 27x27", 2021

Snowflakes dissolving in their own sticky blood, Oil on canvas, 28x31", 2024

It was dark inside the wolf, Oil on canvas, 48x60", 2022

Cinetic big ball, Oil on canvas, 10x15", 2022